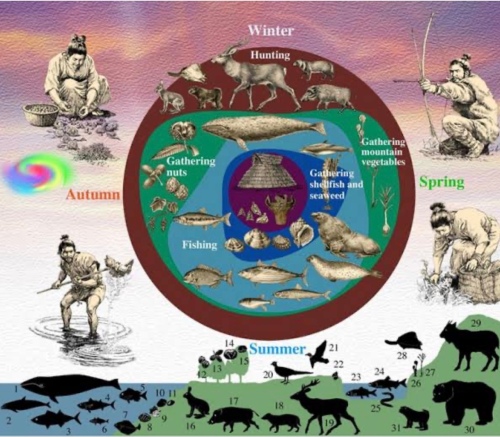

Some scholars have come up with a Jomon calendar that to summarize the seasonal rounds and patterns of activities that the Jomon people engaged in for their survival. It corresponds to the foods that are available naturally during the different times of the year. Jomon activities are thought to have been organized like this:

In the early spring and continuing into summer:

Coastal Jomon people in Eastern Japan are busy fishing the species of fish that come into the estuaries. From excavated shell middens along the eastern Pacific coastal regions, there is proof that the Jomon people preferred catches of snapper (Chrysophrys major), black snapper (Acanthopagrus schlegeli), and sea bass (Lateolabrax japonicus).

Shellfishing, for clams (Meretrix lusoria), shortnecked clams (Tapes japonicus), corbiculae (Corbicula. japonica) and granular ark (Tegillarca granosa), is carried out mostly from spring to summer. Jomon shell middens show that the shellfish deposits decreased gradually in later summer and autumn, and that no shellfishing was carried out during winter. People also probably caught salmon in summer and autumn (but perhaps because the bones are finer, very little salmon has showed up in the middens so far).

In the summer, fishes normally found in the open ocean such as mackerels, tunas (Thunnus sp.) and bonitos (Katsuwonus sp.) – those of the family Scombridae, are caught as they migrate along the rocky-shore zones during this season. Such fishes are commonly found in Jomon shell middens of the Tohoku district. In places such as Hokkaido, sea mammal hunting (whale and dolphin) is carried out intensively in the summer.

People living along the estuaries, inlets or bays in eastern Japan as well as in northern coastal areas facing the Pacific ocean, are not only able to obtain food from the sea, but they also gathered in spring, edible plant foods like ferns, bamboo shoots and other leaf buds. From the forest, around 300 kinds of edible plants could be found.

In the autumn, gathering and collecting food from the forest was an important strategy for survival and for a stable settled lifestyle for Jomon people living everywhere. Particularly abundant foods in the forest after the climate became warmer following the Early Jomon period, were chestnut (Castanea crenata), walnut (Juglans mandshurica), hazelnut (Corylus sieboldiana), and acorn (Castanopsis cuspidata). Many Japanese archaeologists believe the Jomon people tended or nurtured chestnut and walnut trees and other plants near their settlements.

In Jomon settlements everywhere, underground storage pits have been found, often containing large stores of all sorts of nuts and acorns. Additionally, they also collected berry, mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera) fruit and wild grapes. Gourd (Lagenaria sp), gram or shiso beefsteak herb (Perilla sp) were also collected but these were not important to the diet, probably used to supplement the diet or to prepare ceremonial foods. Some roots, bulbs and tubers could be collected all year round.

For Jomon people living in the west and in the eastern interior, in areas between freshwater rivers or streams, marshes or lakes, and mountainous laurel or deciduous forests, the collecting of edible plant foods and hunting of land mammals was absolutely vital. This was because they did not have backup supplies of seafood from estuaries, bays or the open sea.

In winter, hunting was carried out most intensively. Although the Jomon people probably hunted wild boar and deer during other seasons of the year to supplement their food supply, they hunted more of these animals later in the year (from October to December). This is because wild boar and deer form large herds during the winter season. From examining the middens (or their kitchen dumps), it is clear that more wild boar was caught than deer.

References:

Photos of exhibits at Tama Center’s Jomon Village Archaeological Center, credit: Heritage of Japan (this website)

Jomon seasonal calendar attributed to Junko Habuka The Ancient Jomon of Japan, Photo here is courtesy of An online resource of Japanese archaeology and cultural heritage

Thanks for the info !

Fantastic history

… My understanding is Jōmon were the start of settled/ civilisation… More permanent settlements, homes, and the birth of agriculture and you say even including rice? And taro? Didn’t taro then head out into the Pacific?

Thank you.

There were only a very few very large trading settlements with calendrical monuments, complex religion, art, culture, incipient agriculture, some elementary ditch engineering, carpentry techniques and road building, whether they can classified as sedentary settlements (yes, absolutely); civilisation – depends on whether your definition includes writing see https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/civilizations/(Cahokia and Inca were considered civilizations although they did not have writing https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ece3.6958) The Jomon was more like the Cahokia and Japan did not have writing until writing culture arrived relatively late from the continent during the protohistoric Kofun (possibly Yayoi period)

Taro – origins likely in Southeast Asia. Oldest wild cultivars CI, Type 1 haplotype has the widest distribution under cultivation and are common in cultivated taros from Africa to Asia and Remote Oceania, Asia, Africa and Pacific; the oldest wild cultivar CI, Type 1 haplotype appears to be very widespread among commensal wild taros used as food and as fodder in household pig husbandry (mainland and island Southeast Asia to Okinawa in southern Japan). All evidence points to the Type 1 taro in Kimberley representing a prehistoric introduction from island Southeast Asia by early agriculturalists, hunter-gatherers or sea-faring traders, the diversity of types in Japan is very very low, sampling shows almost entirely of the wild cultivar (the chart is helpful see Evolutionary origins of taro (Colocasia esculenta) in Southeast Asia – https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ece3.6958 ) It’s highly probable taro arrived earlier than the Austronesian dispersal of taro into the Pacific.