1,500 year old Gaya Kingdom girl revealed

More from the Korea Times:

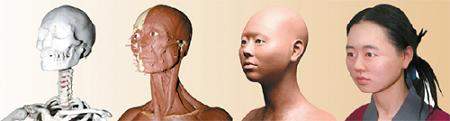

A life-size model of a young girl from the 6th-century Gaya Kingdom (42-562) was revealed in Seoul, Wednesday. The model, constructed from the “1,500-year-old’s” excavated skeletal remains, is the first of its kind in the country.

“We have excavated human bones on many occasions but it is the first time we created a full-scale model,” Kang Soon-hyung, director of the Gaya National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, was quoted as saying by the Munhwa Ilbo.

The girl, who was buried alive, is speculated to have been a 16-year-old servant to a powerful family. After adding layers of muscle and skin as well locks of hair, the model stands 1.53 meters tall. She is relatively short but is slim and has a small face ― a beauty by modern standards.

Her remains were among those of four people that were unearthed during the institute’s excavation project in Songhyeong-dong, Changnyeong-gun, South Gyeongsang Province, between 2006 and 2007. A study on Gaya’s custom of burying the living with the dead will soon be published, the institute said.

The life-size model marks the highlight of the study, in that it allows a scientific and realistic restoration of an ancient Korean. She had a short jawbone and thus had a rather wide face but had a long neck; she had short arms but long fingers and toes. She was very slim, with a waist measuring 21.5 inches, compared to the modern average of 26 inches. The upper half of her body was large compared to her lower half. It is also speculated that she knelt on her knees frequently.

The restoration is the culmination of interdisciplinary work in the fields of archaeology, forensic medicine, anatomy, genetics, chemistry and other fields two years in the making, JoongAng Daily wrote.

“We rarely find bones in such a good condition from the era because soil in Korea is really rich,” said Lee Seong-jun, a researcher at the institute. “There have been restorations, but most of them were based on the imagination. This case, however, is strictly based on medical science, somatology and statistics.”

The servant girl is thought to have spent long periods kneeling and engaging in repititious tasks cutting something with her teech, which was analyzed to estimate her age. She was found with a golden earring and is believed to have died from soffocation or poisoning. Her main diet had been rice, barley, beans as well as meat.

Various funerary customs were followed before, during and after burials. After the burial service, earthenware used in the service was either buried in the tomb or broken into pieces and buried separately near the tomb. The former practice perhaps symbolized the living’s condolences, while the latter practice may have been intended as an affront to death itself. The burial of intact earthenware implies sorrow for and dedication to the dead, while the burial of shattered earthenware suggests severance from the dead.”

Please clarify my doubts.

Many korean words and Tamil words are similar.

Moreover culture traditions are also having similarities.

Example:

Ceremonies done while planting crops and ceremonies done after harvesting ( “adi perukku function” and “pongal function” in Tamilnadu)

In tamilnadu there are stories like marrying Tamil Ayota princess to far eastern dynasty.

Is it anything true?

According to the founding legend of Geumgwan Gaya recorded in the 13th century texts of the chronicle Garakguk-gi (hangul: 가락국기, hanja: 駕洛國記) of Samguk Yusa, King Suro was one of six princes born from eggs that descended from the sky in a golden bowl wrapped in red cloth. Suro was the firstborn among them and led the others in setting up 6 states while asserting the leadership of the Gaya confederacy. Also according to legend, King Suro’s queen Heo Hwang-ok was a princess from a distant country called Ayuta (아유타, 阿踰陀; variously identified with Ayodhya in Uttar Pradesh, India or Ayuhatta in Thailand.

Strangely enough, there appears to be East Asian genes among Tamils too *see this chart https://www.quora.com/Are-Tamil-Brahmins-considered-a-different-race-from-other-Tamils

Similarity in language especially that of rice agriculture is believed to be due to the spread of early Austroasiatic rice cultivators of southeast Asia see Chaubey’s research, Population Genetic Structure in Indian Austroasiatic Speakers: The Role of Landscape Barriers and Sex-Specific Admixture https://academic.oup.com/mbe/article/28/2/1013/1220271

More theories here

Koreans trace their origin to India http://genworldnews.blogspot.com/2016/07/koreans-trace-their-origin-to-india.html

The symbolism behind the golden egg from which Brahma and King Suro emerged https://japanesemythology.wordpress.com/notes-the-symbolism-behind-the-golden-egg-from-which-brahma-and-king-suro-emerged/

The twin fish state symbol https://japanesemythology.wordpress.com/the-twin-fish-which-is-the-state-symbol-of-uttar-pradesh-found-on-ancient-buildings-of-ayodhya-is-the-biggest-clue-to-the-link-and-the-route-undertaken-by-kaya-karagaya-royals-to-korea-and-japa/

Pingback: 10 People Who Were Buried Alive – Articels

The Queen’s(Heo Hwang-ok) DNA test results indicate that she is from south india and not from North.

Pingback: Diez personas que fueron enterradas vivas – internetsano.do

Visit https://youtube.com/c/drnkannan for more details on Korea Tamil connections.

Inconclusive. Megalithic burial jar culture is spread over a wide area in Asia and over very long period but they are generally acknowledged to be closely related to the Austronesian culture. The Korean Gaya may not have originated from Tamil India but from an upstream Central Asian common Austronesian or proto-Austronesian ancestor. Migrational history of ancient lineages of ancient Indians is still being revealed.

See (2022) The HLA profile and genetic affinities of three primitive Tamil-speaking endogamous groups: Kallars of Thanjavur, Piramalai Kallar and Vanniyar

https://jmhg.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s43042-022-00378-7#Abs1From time immemorial, Central Asia is thought to be an important reservoir of genetic diversity and the source of at least three major waves of migration leading into Europe, the Americas, and India [1]. We recently established that two Tamil-speaking populations of the South India, the Mukkuvar, an endogamous group from coastal regions of South Tamil Nadu state, …and the Valayar, a group inhabiting predominantly inland hilly regions with forest cover, are related to Austronesian and Micronesian populations [2].

The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) polymorphism in human populations has been studied for long to investigate immunogenetics, human genetic relationships and in reconstructing past migrational histories of populations. The extensive allelic variation among the HLA class I and class II genes distinguishes these as the most polymorphic coding sequence loci in the human genome [3]. The analysis of these genes has been a valuable tool in unraveling the historical relationships between ethnic groups and has greatly increased the knowledge of the ancestry and migration patterns of many populations including various endogamous groups in South India. the alleles of the HLA class II (DRB1, DQB1) loci in three primitive Tamil-speaking Dravidian endogamous population groups such as Kallars of Thanjavur, Piramalai Kallar (of Madurai) and Vanniyar. Furthermore, the DNAs of most common two-locus haplotypes, such as DRB1*15-DQB1*06 and DRB1*07-DQB1*02 were typed for HLA-A, -B and -C alleles to identify the possible 5-locus extended haplotypes (EH) in these population groups. The frequencies of HLA-DRB1 and DQB1 alleles and haplotypes and phylogenetic relationships of these populations with nineteen other global populations are also constructed and discussed.