During the Nara Period, Buddhism had already gathered momentum in Japan and the number of priests and nuns had increased greatly as well. While in the early years Buddhist clerics were governed by high-ranking priests known as sogo – chosen with considerable autonomy by the Buddhist community, over the years and by 701, the imperial court issued more and more sets of regulations to govern priests and nuns and their daily lives and personal activities. Collectively, these regulations were called the Soni Ryo and Provision Article 27 of Yoro Soni Ryo made it clear that the government sought to prohibit preaching outside temple precincts and to force priests and nuns to live and work within their religious communities.

During this time, there flourished in Nara six major well-known schools of groups of teachers and students who focused each on a particular doctrinal system of study. All of these academic schools were affiliated to Todai-ji Temple and were the “officially recognized” religious centres, signifying the central importance of the Todaiji Temple. However, Nara Buddhism encompassed more than these six schools and the temples of Nara Buddhism were not exclusively affiliated with any school.

Apart from the centrally authorized schools of Buddhism, there existed the so-called “mountain Buddhism” movement. Furthermore, some Nara Period priests devoted themselves to religious life in remote mountain temples such as Hiso-dera (or Hoko-ji) in the Yoshino district of the Yamato Province. Priests who had gained extraordinary powers as a result of religious practice in such isolated spots often went on to become influential special ritualists at court or at major temples. This movement of Buddhism called mountain Buddhism provided a great stimulus for the development of Nara Period Buddhism and its magical practices ranked as one of the pillars of Buddhism along with the academic practices and studies pursued at one of the official temples of the period. (However, it should be noted that apart from Buddhism, the people also practised at the time shamanist magical practices from the continent, indigenous pre-Buddhist magic as well as the Chinese Taoist magical practices that were also very popular).

There arose a kind of popular practical Buddhism that was quit e unnconnected with the officially rcorganized temples. Two such privately ordained monks associated with mountain Buddhism were Taicho (682-767) known as the Great Sage of Koshi and En no Gyoja of Mt Katsuragi. Such monks did not conform to the manners and standards of the capital and so were rejected by the secular and religious authorities as undesirables. The closer they were to the people, the more severely they were persecuted by the authorities usually on two grounds: – for being privately ordained, and by their popularity for disturbing the status quo of church and state. They were also accused of going into the mountains on their own and of setting up hermitages and of abiding in isolated spots and pretending to teach the Law of Buddha.

Below we feature two well-known monks who lived during this religious climate of the Nara Period – Ganjin and Gyoki, their lives and their exploits.

Ganjin (688–763)

Ganjin (in Japanese or Jianzhen as he was known in Chinese) was a Chinese monk born (in present day Yangzhou, Jiangsu) who helped to promote and propagate Buddhism in Japan. He had entered the Buddhist Daming Temple (大明寺)at age 14, studied in Chang’an at age 20 and returned 6 years ago to become the abbot of Daming Temple. Ganjin is also said to have been well-versed in medicine and to have created a hospital within Daming Temple.

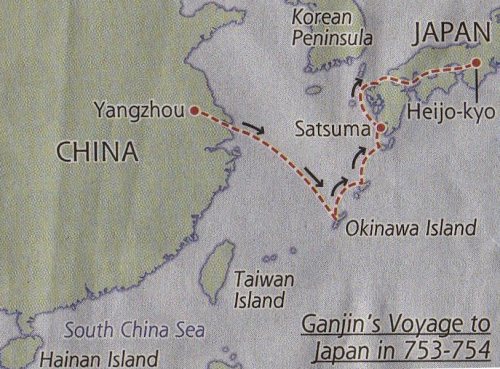

In the eleven years from 743 to 754, Ganjin attempted to visit Japan some six times. In autumn 742, an emissary from Japan invited Ganjin to lecture in his home country. Despite protests from his disciples, Ganjin made preparations and in spring 743 was ready for the long voyage across the East China Sea to Japan. The crossing failed and in the following years, Ganjin made three more attempts but was thwarted by unfavourable conditions or government intervention.

In summer 748, Ganjin made his fifth attempt to reach Japan. Leaving from Yangzhou, he made it to the Zhoushan Archipelago off the coast of modern Zhejiang. But the ship was blown off course and ended up in the Yande commandery on Hainan Island. Ganjin was then forced to make his way back to Yangzhou by land, lecturing at a number of monasteries on the way. Ganjin travelled along the Gan River to Jiujiang, and then down the Yangtze River. The entire failed enterprise took him close to three years. By the time Ganjin returned to Yangzhou, he was blind from an infection.

In the autumn of 753, the blind Ganjin decided to join a Japanese emissary ship returning to its home country. After an eventful sea journey of several months, the group finally landed at Kagoshima, Kyūshū on December 20.

Ganjin reaches Nara

Ganjin finally reached Nara (奈良) in the spring of the next year 754 and was welcomed by the Emperor.

At Nara, Ganjin presided over Todaiji (東大寺) and helped to ordain hundreds of monks.

In 759 the imperial court granted Ganjin a piece of land in the western part of Nara. There he founded a school and also set up a private temple, Toshodaiji (唐招提寺).

In the ten years he was in Japan, Ganjin not only propagated the Buddhist faith among the aristocracy, but also served as an important conductor of Chinese culture. He is credited with having introduced Ritsu Buddhism or monastic rules to Japan. The Chinese monks who travelled with him introduced Chinese religious sculpture to the Japanese.

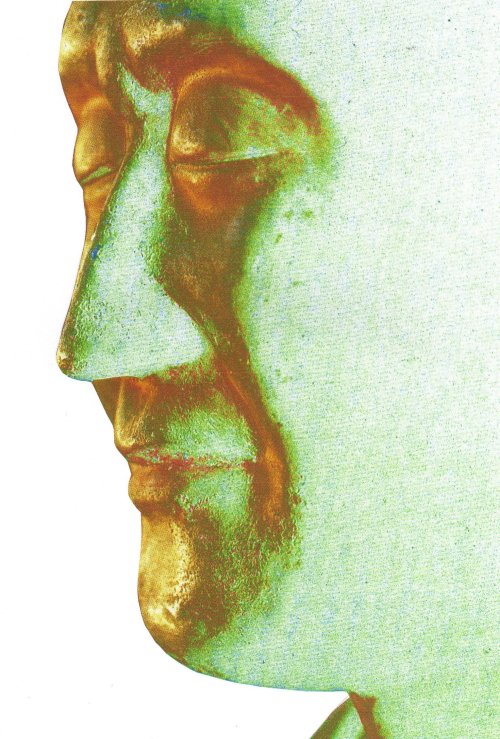

Ganjin died in 763. A famous dry-lacquer statue of him made shortly after his death (and therefore thought to be in his likeness) can still be seen in his temple at Nara. Recognised as one of the greatest of its type.

Gyōki, Bodhisattva of Japan (668-749)

Gyoki was born in 668 in Ōtri county, Kawachi Province (southern Osaka), to family of Korean Paekche descent.

Gyōki took Buddhist vows at age 15, entering Asukadera in Nara (founded in 569) (alternative version:theology at the Kandai-ji temple, studied Buddhism from Dosho and Gien at Yakushiji temple). However, though employed by the government as an official priest, he was not satisfied with the prevailing form of Buddhism which he saw as benefiting the welfare of the court nobles, and not the masses. He then quit his official job in 704 at age 36 to propagate Buddhism for salvation of the suffering people and to practice philanthropy,traveled through different provinces to preach Buddhism and making pilgrimages mostly in Osaka and Nara areas.

Gyoki is best remembered for his efforts to help the poor mainly in Kansai region, for roaming the countryside propagating the teachings together with farming techniques to oppressed people hungry for both and for building 49 monasteries and nunneries that functioned as hospitals for the poor. Gyoki was arrested since his activities, which contravened secular laws, were carried out in a time when the government maintained strict control of Buddhists by confining them to temple grounds for academic study. Besides being perceived as an uncontrolled spiritual power, Gyōki’s arrest was likely related to reports of huge gatherings of rural people he was organizing. This was seen as an imminent political threat to the instable power of the capital.

Though persecuted for troubling peasants, Gyoki was nevertheless given a pardon, perhaps as the government realized his popularity (the people called him ‘Gyoki Bodhisattva’) and sought to harness it instead and soon Gyoki came to influence Emperor Shomu (701-756) and to play a key role in the building of the Todaiji temple. Emperor Shomu had planned to construct a great Buddha statue in Nara but the project was so huge that state funds alone were not enough to cover the total cost. So the emperor sought Gyoki’s help to raise funds. Accepting the emperor’s request, Priest Gyoki immediately began fund-raising campaigns. His philanthropic activities are thought to have mobilized support so that enough alms were collected soon afterward, enabling the casting in 752 of the bronze Great Buddha statue at Todaiji was able to be completed.

During the construction of Todaiji Temple, the government recruited Gyōki and his fellow ubasoku monks to organize labor and resources from the countryside. He also produced constructions of several ponds. He also contributed to social welfare building roads, bridges, irrigation dykes, ponds and reservoirs and other civil engineering projects, and helped construct a number of temples.

As such, Gyoki came to achieve great fame as a Buddhist philanthropist.

Unfortunately, he had passed away just before the consecrating ceremony for the statue took place. In praise of the priest’s achievement, the emperor conferred on him the title of Dai-sojo, or the Great Priest, the highest rank given to priests.

Related links:

Imperial envoys made perilous passages on kentoshi-sen ships to Tang China

In the news: Kentoshi ships to reenact ancient voyages

In the news: The lasting impact of the monk Ganjin’s voyage on Japan

See Image of bronze statue of Gyoki in Osaka

Sources:

A biography of the life and legacy of the Bodhisattva Gyōki by Ronald S. Green

The Ancient Buddhist stories and Gyoki [in Japanese:古代仏教説話と行基]

A History of Japanese Religion by Kazuo Kasahara (ed.)

Related web sites: http://www.asahi-net.or.jp/~sg2h-ymst/gyouki.html; http://www.spi.ne.jp/~jgg4450/garyu-ii/index-i.htm; http://www.city.koga.ibaraki.jp/rekihaku/2001haru/p1.htm; http://www.asahi-net.or.jp/~QM9T-KNDU/Hinatayakushi.htm;

http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/monju.shtml#gyoki

© Heritage of Japan