Here, I’d like to highlight data from two papers about the prehistoric dispersal routes of barley from Eurasia into Hokkaido. From the first, Lister 2018, I draw our attention to the proposed routes by which mainly six distinctly different types (and distributions) of domesticated barley arrived from the west to Eastern Eurasia into the terminal end in Japan. Note in particular the two different routes of barley into Japan: The northern route into Hokkaido via Sakhalin Island vs. the route from the Chinese coast to southwestern Japan in Lister’s map below.

Proposed routes of spread of six types of domesticated barley (vulgare) genepools Source: Lister, 2018

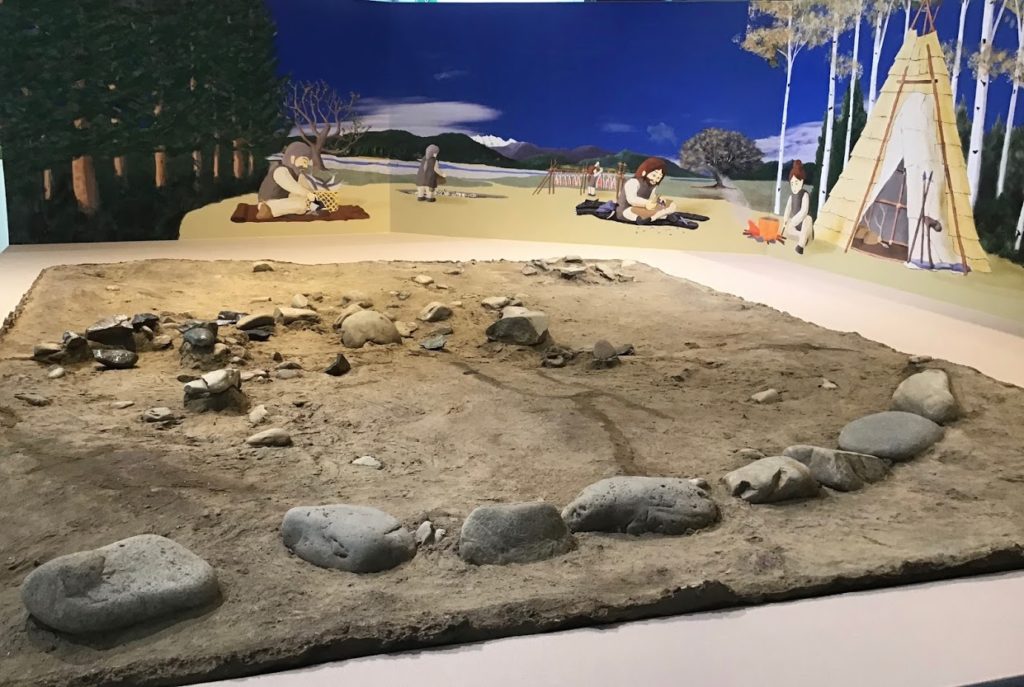

The second paper by Leipe et al, see the excerpted analysis that follows below considers new evidence about the little known Okhotsk culture, who were migrants who came from the north through Sakhalin Island (likely from the Lower Amur/Russian Far East region) to Hokkaido, between 600~1000 AD. While the Okhotsk people were known to have intensively exploited marine resources, this study considers new evidence that they supplemented their marine diet with a far wider range of foods than marine resources including terrestrial mammals such as deer, fox, rabbit, and marten, domesticated pigs and dogs as well as edible wild plants including Aralia (spikenard), Polygonum(knotweeds), Actinidia (Chinese gooseberry), Vitis(grapevines), Sambucus (elderberry), Empetrum nigrum(crowberry), Rubus sp. (blackberry), Phellodendron amurense (Amur corktree), and Juglans (walnut). In addition to broomcorn millet, foxtail millet, the paper considers whether the evidence of the new type of barley grains that they brought with them could have been cultivated for agriculture, for ritual use, or on a lighter scale.

This paper is significant as it extends our knowledge beyond what is known about the intensive marine resources subsistence strategy of the Okhotsk culture, based on its study of botanical samples from the Hamanaka site on Rebun Island. In particular, researchers observed that there are two distinctive phenotypes of barley grown in Hokkaido and that clear boundaries are observed of cultivation between the Satsumon hulled barley in the south and the naked barley grown by the Okhotsk culture. Consequently, a picture emerges on the different origins and interactions of the Okhotsk vs Satsumon cultures: the cultivation by the Okhotsk culture of naked barley over 500 years, and the arrival and expansion of the Satsumon with hulled barley towards the 10th ~11th centuries, reflect the pattern of interactions between the two cultures, and as well as evidence of the timing of the arrival and expansion of the Yayoi people into Hokkaido (click to see Leipe et al.’s Fig 1 map).

The 2017 paper by Leipe et al., Barley (Hordeum vulgare) in the Okhotsk culture (5th–10th century AD) of northern Japan and the role of cultivated plants in hunter–gatherer economies

This paper discusses archaeobotanical remains of naked barley recovered from the Okhotsk cultural layers of the Hamanaka 2 archaeological site on Rebun Island, northern Japan. Calibrated ages (68% confidence interval) of the directly dated barley remains suggest that the crop was used at the site ca. 440–890 cal yr AD. Together with the finds from the Oumu site (north-eastern Hokkaido Island), the recovered seed assemblage marks the oldest well-documented evidence for the use of barley in the Hokkaido Region. The archaeo-botanical data together with the results of a detailed pollen analysis of contemporaneous sediment layers from the bottom of nearby Lake Kushu point to low-level food production, including cultivation of barley and possible management of wild plants that complemented a wide range of foods derived from hunting, fishing, and gathering. This qualifies the people of the Okhotsk culture as one element of the long-term and spatially broader Holocene hunter–gatherer cultural complex (including also Jomon, Epi-Jomon, Satsumon, and Ainu cultures) of the Japanese archipelago, which may be placed somewhere between the traditionally accepted boundaries between foraging and agriculture. To our knowledge, the archaeobotanical assemblages from the Hokkaido Okhotsk culture sites highlight the north-eastern limit of prehistoric barley dispersal.Seed morphological characteristics identify two different barley phenotypes in the Hokkaido Region. One compact type (naked barley) associated with the Okhotsk culture and a less compact type (hulled barley) associated with Early–Middle Satsumon culture sites. This supports earlier suggestions that the “Satsumon type” barley was likely propagated by the expansion of the Yayoi culture via south-western Japan, while the “Okhotsk type” spread from the continental Russian Far East region, across the Sea of Japan. After the two phenotypes were independently introduced to Hokkaido, the boundary between both barley domains possibly existed ca. 600–1000 cal yr AD across the island region. Despite a large body of studies and numerous theoretical and conceptual debates, the question of how to differentiate between hunter–gatherer and farming economies persists reflecting the wide range of dynamic subsistence strategies used by humans through the Holocene. Our current study contributes to the ongoing discussion of this important issue...

People in northern Japan, similar to those in Greenland, Arctic regions of Asia, and the American West Coast, remained “complex” hunter–fisher–gatherer well into the historic period [19]. Local Jomon populations of Hokkaido continued a foraging lifestyle [20] until the middle of the 1st millennium AD when they were replaced[?] by Okhotsk cultural communities in the north and by Satsumon cultural communities in the central and the southern parts of the island [21]. Both of the latter cultures are commonly identified as hunter–fisher–gatherers [19]; however, their archaeological remains show evidence for the use of metals and the cultivation of crops [8]. The extent of their productive economy has not been fully studied. To date, the only clear evidence for the cultivation of barely and other crops by Satsumon people in the late 1st millennium AD comes from a single excavation site, which is located in the municipality of Sapporo [8]. There are more data showing that their contemporary neighbours to the north, the Okhotsk culture in Hokkaido, were cultivating both broomcorn (Panicum miliaceum) and foxtail (Setaria italica) millet and barley [8]. However, there have only been a few archaeobotanical studies on Okhotsk sites in Hokkaido and they are entirely published in local Japanese periodicals (e.g. [22, 23]), which are often not available to the international scientific community….

The Okhotsk CultureThe people of the Okhotsk archaeological culture are regarded as a hunter–gatherer society with an economy that strongly relied on marine resources. They occupied a widespread maritime environment, mainly along the southern and eastern littoral margins of the Sea of Okhotsk including northern and north-eastern Hokkaido (see Fig 1C for archaeological site distribution), Sakhalin Island, and the Kurils (Fig 1A). In the Hokkaido Region, the peak of the Okhotsk cultural occupation dates from the 6th to the 8th century AD (see [26] and references therein). Based on pottery style, the “Okhotsk cultural sequence” in northern Hokkaido is divided into three chronological stages comprising the (1) Susuya culture (2nd–5th century AD), which is often referred to as incipient or Proto-Okhotsk, (2) the Towada, Kokumon, Chinsenmon, Haritsukemon, and Somenmon cultures (6th–8th century AD) regarded as the main stages, and (3) the Motochi culture (9th–10th century AD) as the final stage [27]. While Okhotsk cultural traits persisted through the Tobinitai period in eastern Hokkaido until the 12th century AD, replacement or assimilation of the Okhotsk culture in northern Hokkaido by Satsumon/Proto-Ainu populations originating from the central and southern areas of Hokkaido was completed by the end of the 10th century AD …Archaeologists believe that the Okhotsk culture people migrated to Hokkaido from the north (i.e. Sakhalin Island), first occupying Rebun and Rishiri islands as well as the northern tip of Hokkaido and subsequently dispersing eastwards along the coast of the Sea of Okhotsk [28]. Results of archaeological and genetic studies suggest that the Okhotsk population probably originated from the lower Amur River basin (e.g. [29–31]). The population spread onto the islands bordering the Sea of Okhotsk, which is believed to have been due to socio-political conflict [31]. There is also evidence for the onset of cooler climatic conditions in the lower Amur River basin around the end of the 1st millennium BC [32, 33]. These climate changes may have played a role in the southward spread (ca. 500 AD) of these people to Hokkaido [34] and their later absorption/replacement (by ca. 1000–1200 cal yr AD; [26, 27]).

A defining trait of the Okhotsk culture is its subsistence strategy, traditionally thought to be a specialised system of marine resource extraction [26, 35]. This is reflected by the geographic distribution of sites along coastal regions (Fig 1C) and confirmed by archaeological studies of faunal remains and tool assemblages, which indicate intensive marine hunting, fishing, and gathering activities (e.g. [31, 36, 37]). Nitrogen stable isotope studies on human remains also point to a diet with high proportions of protein derived from marine organisms (e.g. [35, 38, 39]). Analysis of human bone collagen revealed a relative contribution of marine protein in the range of 60–94% for individuals from Rebun Island and 80–90% for individuals from eastern Hokkaido [39]. However, there is enough evidence to suggest that the diet of the Okhotsk people may have been much more diverse than the isotopic data imply. People likely supplemented the maritime resources with terrestrial mammals such as deer, fox, rabbit, and marten [37]. Cut marks on bones from domesticated dogs suggest that they were also part of the diet [36], and remains of domestic pigs are limited to northern Hokkaido [26]. In addition, there is evidence for the use of edible wild plants including Aralia (spikenard), Polygonum(knotweeds), Actinidia (Chinese gooseberry), Vitis(grapevines), Sambucus (elderberry), Empetrum nigrum(crowberry), Rubus sp. (blackberry), Phellodendron amurense (Amur corktree), and Juglans (walnut). Furthermore, as already noted, broomcorn millet, foxtail millet, and barley grains have been recovered from sites in this cultural horizon (see [26] and references therein). Admittedly, we know very little about the role of any of these plants in the economy, or whether the crops had a dietary or ritual function. ….

Within the RFE, 15 sites are situated in southern Primor’e (Fig 1B, no. 2–16) and one in the western Amur River valley (Fig 1A, no. 1). The Primor’e sites are associated with early Iron Age Yankovskaia (ca. 850–350 cal yr BC) and Krounovskaia (ca. 500 cal yr BC–200/300 cal yr AD) cultures, the Iron Age Ol’ginskaia culture (ca. 300 cal yr BC–300/400 cal yr AD), the early medieval Mohe culture (ca. 5th–11th century AD), the Bohai State (698–926 cal yr AD), the period following the defeat of the Bohai State (10th century AD), and the Eastern Xia State (1215–1233 AD). The barley finds from the western Amur River valley site represent Troitskii variant of the Mohe culture (end of 8th–9th century AD). From these sites there are in total 25 barley records of which 17 contain measurement data for individual grains. The number of grains per record ranges from 1 to 40. … A total of eleven samples of archaeobotanical barley from south of the Okhotsk culture domain were also considered in this study. They originated in the Hokkaido Region from Early to Middle Satsumon culture (Fig 1C, no. 17–24) and northern Tohoku Heian period (Fig 1C, no. 25–27) sites and date to 8–10th and 9–11th centuries AD, respectively. Scholars have suggested that during the Okhotsk Tobinitai stage (11th–12th century AD; [26]), which emerged in the north-eastern part of Hokkaido, there were enhanced interactions with Late (ca. 1000–1200 cal yr AD) Satsumon groups [54]. Therefore, the review of Satsumon barley is limited to the early and middle stages. The information available for the Early and Middle Satsumon sites (n = 8) is restricted to mean values for L/W ratios, which vary between 1.65 and 2.58 with an average of 2.16. Absolute numbers of measured seeds are not provided in the publications, except for one site (Fig 1C, no. 24). Information from northern Tohoku is based on measurements of three assemblages containing 2, 7, and 50 barley specimens. Their length to width ratios equate 2.3, and their median is 2.29.

For Early and Middle Satsumon barley assemblages information on grain shape (i.e. L/W ratio) is only available in the form of arithmetic means, a statistic which is sensitive to outliers. However, these values are, with one exception, all within the inner whiskers of box-plots of the L/W values for barley from northern Tohoku sites (Fig 4), thus regarded as representing comparable barley varieties. One notable exception is the relatively low mean value of 1.65. Given its small population of five grains and strong offset to the other means, this sample may be regarded as an outlier. The results delineate that the charred barley seeds recovered from Okhotsk culture sites are the most compact. Although still plumper, they are more comparable in shape to grains from the RFE than to those found in Satsumon sites on Hokkaido and Heian period sites in northern Tohoku. While the barley from south of the Okhotsk domain appears to be longer and narrower, the Okhotsk culture and RFE varieties are more compact. The differences in L/W ratio indicate that the long grains comprise hulled and the compact ones naked barley. The ‘nud‘ allele for naked barley is monophyletic [55], thus genetically distinct from hulled barley. This implies a sharp difference between the barley that was grown in these different regions.

DiscussionThere is evidence that human migrations from the north have played an important role in the prehistory of Hokkaido and other parts of the Japanese archipelago. This includes the intrusion of Siberian Palaeolithic hunter–gatherer groups around the Late Glacial Maximum (ca. 20,000 cal yr BP; [60]) and immigration ca. 15,000 cal yr BP, with the latter introducing microblade technologies on Hokkaido and Honshu [61, 62]. While they have not been taken into account for a while (e.g. [63]), recent anthropological studies (e.g. [64]) stress the role of migration from northern regions via Hokkaido also in view of the origins of the Neolithic Jomon culture. The most recent southward movement of prehistoric populations into the northern and north-eastern coastal areas of Hokkaido was that of the Okhotsk culture around the middle of the 1st millennium AD [26]. Though, the Okhotsk groups inhabited a large area along the southern and eastern margins of the Sea of Okhotsk, most of our current knowledge has been derived from archaeological materials recovered in the Hokkaido Region. The archaeobotanical record from the Hamanaka 2 site presented in this study allows for greater insight into the use of plants by the Okhotsk people on Rebun Island (Fig 1D). Calibrated ages (95% confidence interval) of directly dated barley remains from five archaeological layers (IIIa–e) suggest that the crop was used at the site between 430–960 cal yr AD (Table 2) or at a 68% confidence interval between ca. 440 and 890 cal yr AD. This time period roughly corresponds to the late Susuya through mid-Motochi stages spanning between the 5th and 10th century AD [27], thus covering the Okhotsk culture settlement phase in northern Hokkaido as indicated by previous archaeological studies. Given the age of the oldest barley seed F2014-037-003 (440–600 cal yr AD, 68% confidence interval; Table 2), the Hamanaka 2 layer IIIe, together with the single dated grain (428–573 cal yr AD, 95% confidence interval; [65]; S3 Table) from the Oumu site (no. 29 in Fig 1C) represents, the earliest well-documented record of domesticated barley in the Hokkaido Region. The only carbonised barley grain recovered in Hokkaido was collected from the Epi-Jomon level of the K135–4 Chome site within the city of Sapporo [66]. This single barley seed has not been directly dated and its proposed age of ca. 200–400 cal yr AD should be viewed with caution.

The presence of barely at the Hamanaka 2 site appears contemporaneous with a phase of enhanced human-induced vegetation disturbance on Rebun Island as indicated by the pollen record from Lake Kushu (Fig 5). During this time (with a maximum ca. 550–800 cal yr AD), the pollen record shows a decrease in the abundance of arboreal pollen, suggesting deforestation and greater openness of the landscape compared to the preceding and subsequent periods, which are more or less coeval with the Epi-Jomon and Proto-Okhotsk (Susuya) cultures (ca. 100 cal yr BC–500 cal yr AD) and Proto-Ainu culture (ca. 950–1600 cal yr AD), respectively ([26, 27]; Fig 5). The results of the local vegetation reconstruction clearly indicate enhanced human activities on Rebun Island during the main phase of the Okhotsk presence there. On the other hand, reduced impact is evidenced during the Epi-Jomon phase and the time of cultural shifts towards the Classic Ainu period, which may be explained by reduced population size and/or a different pattern of resource exploitation. Regarding the Epi-Jomon, this would conform to identified traits like short-term occupations, high mobility, and low complexity [66, 67]. Ohyi [28] suggests that by the time of the disappearance of the Okhotsk culture at the end of the Motochi stage, the Satsumon people spread into northern Hokkaido, including Rebun Island and neighbouring Rishiri Island. It appears, at least for Rebun Island, that these Satsumon groups weakly impacted the island’s vegetation, which was leading to the recovery of the local fir forests. … Rebun Island is well-known for its Okhotsk culture sites, representative for the northern Hokkaido domain. Here, the presence of the Okhotsk groups continued into the Motochi stage (9th–10th century AD) at a time when the Okhotsk sites in northern Hokkaido became abandoned [28]. However, on Rebun Island the presently discussed Hamanaka 2 assemblage contains the only barley thus far recovered (T. Amano, personal communication). This might be due to a lack of systematic sampling and water flotation at other sites on the island. We identified the recorded barley as naked barley, which is far more commonly found than hulled barley in East Asia [68]. Barley was consumed at the site over a ca. 500-year period throughout the main stages of the Okhotsk culture (Fig 5). Barley was significant and had a long-term role in diet during the peak of the Okhotsk culture in the region. The use of barley is also evident at other sites in north-eastern Hokkaido (Fig 1C), being assigned to the late phase (8th–9th century AD) of the Okhotsk culture [69]. In addition, remains of foxtail and broomcorn millet are reported from several excavations [69]. Japanese palaeobotanists have argued that these crops were used for ritual purposes (e.g. [22]); however, this is hard to defend seeing that they appear in so many domestic contexts across such a large time period. The grains likely supplemented a mixed economic system that relied heavily on wild coastal resources. Although, an alternative hypothesis is that these crops were used to produce alcohol…

[A diverse subsistence strategy]One reason why some scholars have been hesitant to accept that barley and other cereals were dietary supplements may be that the Okhotsk are generally regarded as a specialised hunter–gatherer culture with a subsistence strongly focusing on maritime food resources. This traditional view of a coastal foraging society has been bolstered by recent human bone isotope studies (e.g. [35, 38, 39]), which revealed a high proportion of absorbed protein derived from marine resources of up to 94% and 90% in northern and eastern Hokkaido, respectively [39]. However, our findings together with results of previous studies illustrate that the Okhotsk relied on a wide range of natural and domesticated foods. Besides the suggested strong focus on marine collecting, fishing, and mammal hunting, the Okhotsk people appear to have employed a broad spectrum of wild terrestrial plant fruits and root tubers (this study, Table 3; [26] and references therein), hunted a variety of terrestrial mammals [37], and also maintained domesticated dogs [36] and pigs [26] as part of their food economy. Indications for plant maintenance also comes from the increase in Lysichiton type pollen in the Lake Kushu pollen record (Fig 5) and carbonised Cyperus sp. root tubers in the Hamanaka 2 flotation samples (Table 3). Both taxa represent plants growing in swampy environments around Lake Kushu, which include edible parts and provide nutritious food. It is conceivable that the local Okhotsk people exploited these plants and even maintained their growth and productivity using suitable tools for tilling as found in contemporaneous cultural strata on Rebun Island [71].

Given the combination of foraging, animal husbandry and the use of barley and other cereals over a wide spatio-temporal array, crop cultivation as a supplementary portion of Okhotsk subsistence seems more plausible. This case study further augments existing examples of (“complex”) hunter–gatherers, occupying the “middle ground” which separates hunting–fishing–foraging societies exclusively depending on wild food resources and agriculturalists with a major focus on managing and producing domesticated plants and animals (e.g. [72, 73]). It has been noted that this middle ground territory is highly complex. As Smith [9] puts it, “this territory between hunting–gathering and agriculture is turning out to be surprisingly large and quite diverse; it has also proven to be quite difficult to consistently describe in even the simplest conceptual or developmental terms”. Smith [74] built his concept of ‘low-level food production’ on earlier observations by Braidwood and Howe [75] as well as Flannery [76], all of whom use the term “incipient cultivation” to describe intermediary strategies between foraging and farming. Many other ethnographers and archaeologists have subsequently noted that there is a wide range of diversity in human economic systems; notably, Boserup [77] points out that the range of land-use strategies reflect an equally broad range of human adaptive economies. There have been different approaches to define the middle ground landscape. Following the conceptual framework of Smith [9], who identified low-level food production (<50% annual caloric budget from domesticates) relating to tended wild plants and/or cultivated/managed plants. The Okhotsk culture may be confidently placed somewhere between the traditionally accepted boundaries between foraging and agriculture. The same view is taken by Crawford [8] who explicitly assumes that the Okhotsk people themselves cultivated barley and millet. Given the evidence for dog and pig husbandry and the cultivation or exchange of barley, the Okhotsk epitomises the complexity and diversity of the middle ground economy. …

… the adoption of domesticates by the Okhotsk people, which occurred in relatively recent prehistory, adds particular value as it bridges the gap between the two foci. Another specific feature of the Okhotsk subsistence strategy is the process of adopting already fully domesticated plants that were, by this time, widely used as staple crops in agrarian societies across Eurasia. In the Okhotsk culture, however, the incorporation of barley and millets does not appear to have had significant socio-economic effects. While the subsistence economy continued to be based on foraging, the society remained egalitarian and “group-oriented” [26]. Similar observations are reported from other regions like Japan as well as Island Southeast Asia and Melanesia. The spread of domesticated rice through the latter two regions appears to have started at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC [81]. However, in most regions, rice remained a minor supplementary crop in subsistence systems mainly based on vegeculture (e.g. taro, banana, and sago production) and foraging [82] until the middle of the 1st millennium AD [83]. In Japan, the oldest botanical remains of domesticated broomcorn and foxtail millet, barley, and rice date between the Middle and Late Jomon periods [17], thus may also indicate an early (pre-Yayoi) introduction of domesticated cereal crops from outside the archipelago as minor subsistence supplements not signifying a fundamental change in dietary pattern.

…the assemblages Okhotsk and Satsumon sites in Hokkaido represent the north-eastern edge of prehistoric barley dispersal across Asia. The upper end (600 cal yr AD) of the calibrated age range (68% confidence interval) of the oldest barley seed contained in the dated Hamanaka 2 sample set is coeval with the onset of the Satsumon culture (beginning 7th century AD), which is believed to have arisen from the Tohoku Region (Fig 1A) Yayoi culture populations driven to Hokkaido by expansion of the first Japanese state [8]. Therefore, the most straightforward inference would be that the barley used by the Okhotsk was derived from Satsumon groups spreading into the central and south-western part of Hokkaido. In fact, previous palaeobotanical work points to a different origin that is further emphasised by the Hamanaka 2 barley seed inventory. In previous studies, Japanese scholars claimed to have identified a short and a long barley type at Okhotsk and Satsumon culture sites in the Hokkaido Region, which they assigned to the crop’s naked and hulled form, respectively (see [69] and references therein). Based on this differentiation and seed morphology, Yamada and colleagues (e.g. [22, 23, 69, 90]) have hypothesised that Okhotsk barley originated from neighbouring regions on the Asian mainland. They found that the highly compact (naked barley) specimens extracted from four Okhotsk culture sites (no. 17–20 in Fig 1C, S3 Table) are distinct from the slimmer (hulled) barley (dated to 8–10th century AD) used by Early and Middle Satsumon groups, but similar to grains identified as naked barley found in the early Iron Age to medieval (ca. mid-1st millennium BC–early 13th century AD) sites in southern Primor’e (RFE). Their morphological comparison of barley grains is based on a length/width ratio dataset. Here, we review their approach by supplementing the available datasets, with eleven (partly unpublished) assemblages from the RFE, three records from northern Tohoku, and the measurements of the Hamanaka 2 site barley (S3 Table). Although naked barley is in general more compact than its hulled counterpart, quantitative morphological comparison allows for objective qualification of the recorded archaeological barley and may provide further confirmation for the proposed Okhotsk barley origin. The Okhotsk barley, which appears to be the most compact of all gathered records (Fig 4, S3 Table), in terms of shape is more similar to its counterparts found in both earlier and later (ca. 850 cal yr BC–1000 cal yr AD) sites located along coastal regions across the Sea of Japan (i.e. southern Primor’e, Fig 1C) and in the Amur River basin (Fig 1A), as opposed to grains recovered from contemporary Satsumon culture sites situated in central and southern Hokkaido. Both the Satsumon and Heian grains, which are morphologically similar to each other, appear generally longer and narrower than those used by the Okhotsk culture. This corroborates Crawford’s hypothesis that the Satsumon culture emerged from the Tohoku Yayoi culture [8], which, when being forced to migrate to Hokkaido, brought their barley with them. Alternatively, this similarity may at least suggest cultural interactions between Satsumon populations and communities in Tohoku. The results also corroborate the hypothesis that the Satsumon type barley represents hulled barely and that the naked Okhotsk barley originated in the continental RFE Region. The minor discrepancies in L/W ratios between the naked barley from Okhotsk sites and sites in the RFE (Fig 4) may reflect morphological differences commonly existing among landrace varieties of crops [91] or may be the result of different environmental conditions or irrigation [92]. This means that the barley used by the Okhotsk culture was either derived by exchange with continental populations (e.g. Mohe culture, Bohai State) from across the Sea of Japan or was brought along and cultivated by the Okhotsk culture from their region of origin (i.e. the lower Amur River basin). Unfortunately, no palaeobotanical studies have been conducted in the lower Amur River basin or on Sakhalin Island, which would have allowed us to trace back potential pathways of a southward barley introduction to Hokkaido. Further evidence for the existence of two barley phenotypes in Hokkaido comes from sites, which post-date the main phase of Okhotsk culture. Both types—the compact (naked) barley found at Okhotsk culture sites and the slim (hulled) barley found at Early to Middle Satsumon sites—are represented in archaeobotanical records from this time indicating that Okhotsk type naked barley cultivation/use continued during times of acculturation (i.e. Tobinitai culture) and the Late Satsumon stage [23]. In sum, these findings suggest that naked and hulled barley spread eastward through Asia and were introduced into the Japanese archipelago via different routes. While the area where hulled barley is recovered parallels the distribution of the Yayoi culture (south-western and central Japan) and the Satsumon culture (south-western and central Hokkaido), naked barley possibly propagated from Primor’e and adjacent regions during the Okhotsk culture spread, into Sakhalin Island and northern/north-eastern Hokkaido (Fig 1A). After the two barley phenotypes were independently introduced to Hokkaido, the boundary between both barley domains (Fig 1A) possibly existed for about 400 years across the island region until the beginning of the assimilation/replacement of Okhotsk populations by the Satsumon culture groups (ca. 1000 cal yr AD; [26, 27]).

Further evidence for a close relationship between the Okhotsk culture and Iron Age/medieval populations from the East Asian continent comes from analogies in subsistence economy as described by Sergusheva and Vostretsov [15]. Like the Okhotsk, the Yankovskaia culture (ca. 850–350 cal yr BC; [15]), which inhabited the coastal regions of today’s northern Korea and southern Primor’e, based its subsistence mainly on a wide range of marine resources. Remains of millets (broomcorn and foxtail) and naked barley found at the majority of sites suggest that these domesticates also played a role in diet there. Primor’e Region, in particular, saw a subsequent two-step advance in agricultural practices by the introduction of additional crops including wheat (Triticum aestivum/compactum), hemp (Cannabis sativa), and legumes during the Krounovskaia/Tuanjie culture (ca. 500 BC–200/300 cal yr AD; [15]) and cultigens including hulled barley (Hordeum vulgare), soy beans (Glycine max), and buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) along with the establishment of early states (e.g. Bohai State) after the middle of the 8th century AD. Despite this progress in agriculture, hunting, fishing, and gathering has continuously been an additional part of the diet. In addition, pig and dog breeding is evidenced during the Yankovskaia culture and the Krounovskaia/Tuanjie culture [71, 93, 94]. These subsistence traits place the above mentioned cultures of coastal RFE and northern Korea also in Smith’s middle ground [9], thus somewhere between hunting–fishing–foraging and agriculture. Systematic water flotation has been practiced for over 30 years in this region, providing archaeobotanical remains from numerous Neolithic–Middle Age sites across Primor’e. These data show that during the Yankovskaia culture, millet and barley cultivation was not the main part of the food economy, and was probably not practiced at every archaeological site [15]. Although crop cultivation seems to have been intensified by the Krounovskaia/Tuanjie culture, there is evidence that these groups, likely due to climatic cooling at the end of the 3rd century AD, partly gave up agricultural practices and re-intensified the exploitation of wild resources [95]. This, on the one hand, emphasises that the transformation towards agriculture is not necessarily a unidirectional progression, as it was once regarded, but is a reversible process. On the other hand, it suggests that crops probably had a long-term utility as complementary foods. This might apply to Okhotsk groups, which retained their once-adopted (low-level) agricultural food production as they migrated and adapted to the maritime landscapes of the Sea of Okhotsk.

Conclusions

The archaeobotanical assemblage from Okhotsk cultural layers at the Hamanaka 2 site (northern Rebun Island, Japan) contained charred grains of compact naked barley. Direct radiocarbon dating indicates long-term use of barley at the site over a period of about 500 years. Together with the finds from the Oumu site, the data that we present marks the oldest well-documented evidence for the use of barley in the Hokkaido Region. Due to the broad error ranges of the calibrated radiocarbon dates of the oldest seed remains (428/440–573/600 cal yr AD, 68% confidence interval), more precise ages cannot be defined at this time. However, it is conceivable that the people of the Okhotsk culture were using this crop since they first arrived in the Hokkaido Region (ca. 500 cal yr AD). Accordingly, barley introduction by the Okhotsk culture would pre-date its adoption or introduction by Satsumon populations by at least a century, which may speak against the hypothesis that barley was introduced to northern Hokkaido by the more agrarian south.

The macrobotanical remains of barley are not enough evidence to argue for cultivation at the site, as opposed to the importing of grains from elsewhere. However, axe- and hoe-shaped bone tools found at nearby sites were likely farming implements and do support the possibility of local cultivation. In addition to low-level cultivation, the archaeobotanical data also suggests that wild plant management was conducted by the people of Rebun Island. The pollen record from Lake Kushu indicates significant local vegetation disturbance (i.e. deforestation) concurrent with the barley record at nearby Hamanaka 2. The reconstructed landscape patchiness may point to land clearance for small-scale crop cultivation. In view of the major role of marine food resources indicated by bone isotope studies, it seems likely that cultivated crops were used as supplementary food or for brewing beer. While future studies will clarify the role of barley in the economy in this region, it does seem clear that there was some kind of low-level crop production, which was complemented by wild foods. …

So far, the archaeobotanical assemblages from the Hokkaido Okhotsk culture sites highlight the north-eastern limit of prehistoric barley dispersal. Seed morphological characteristics identified two different barley phenotypes, which were likely independently introduced to the Hokkaido Region. One highly compact type (naked barley) associated with the Okhotsk culture and a less compact type (likely hulled barley) that is evident in Early–Middle Satsumon culture sites. The much more comprehensive dataset presented in this paper supports earlier suggestions that the “Satsumon type” barley was likely propagated by the expansion of the Yayoi culture from south-western Japan towards north-eastern Japan, while the “Okhotsk type” spread from the continental RFE Region, across the Sea of Japan. Although Okhotsk populations may have obtained barley by exchange, there is growing data that suggest that they cultivated naked barley locally, which they introduced directly from their region of origin (i.e. the lower Amur River basin) via Sakhalin. To further verify this hypothesis, additional palaeobotanical studies on materials from archaeological sites in these areas are essential. Nevertheless, based on existing palaeobotanical evidence, we conclude that the Okhotsk culture represents one element of the long-term and spatially broader Holocene hunter–gatherer cultural complex (including also Jomon, Epi-Jomon, Satsumon, and Ainu cultures) of the Japanese archipelago, which may be placed into Smith’s [9] middle ground subsistence strategy. This middle ground domain may chronologically include the groups dating to the Neolithic–Iron Age interval (ca. 3300 cal yr BC–middle 1st millennium AD) and such cultures as Zaisanovskaia, Yankovskaia, and Krounovskaia of the coastal zone of today’s northern North Korea and the RFE, which share several subsistence traits with the Okhotsk culture..

In previous studies, Japanese scholars claimed to have identified a short and a long barley type at Okhotsk and Satsumon culture sites in the Hokkaido Region, which they assigned to the crop’s naked and hulled form, respectively (see [69] and references therein). Based on this differentiation and seed morphology, Yamada and colleagues (e.g. have hypothesised that Okhotsk barley originated from neighbouring regions on the Asian mainland. They found that the highly compact (naked barley) specimens extracted from four Okhotsk culture sites (no. 17–20 in Fig 1C, S3 Table) are distinct from the slimmer (hulled) barley (dated to 8–10th century AD) used by Early and Middle Satsumon groups, but similar to grains identified as naked barley found in the early Iron Age to medieval (ca. mid-1st millennium BC–early 13th century AD) sites in southern Primor’e (RFE).

Who are the Okhotsk culture people?Takehiro Sato, et al., Origins and genetic features of the Okhotsk people, revealed by ancient mitochondrial DNA analysis J Hum Genet (2007) 52:618–62716 mtDNA haplotypes were identified from 37 individuals of the Okhotsk people. Of the 16 haplotypes found, 6 were unique to the Okhotsk people, whereas the other 10 were shared by northeastern Asian people that are currently distributed around Sakhalin and downstream of the Amur River. The phylogenetic relationships inferred from mtDNA sequences showed that the Okhotsk people were more closely related to the Nivkhi and Ulchi people among populations of northeastern Asia. In addition, the Okhotsk people had a relatively closer genetic affinity with the Ainu people of Hokkaido, and were likely intermediates of gene flow from the northeastern Asian people to the Ainu people. These findings support the hypothesis that the Okhotsk culture joined the Satsumon culture (direct descendants of the Jomon people) resulting in the Ainu culture, as suggested by previous archaeological and anthropological studies. …Skeletons of the Okhotsk people share par- ticular morphological characteristics: high and round neu- rocranium, large mandible, flat face, and extremely shallow canine fossa. Kodama (1948) reported that these characters were similar to those of the Aleut people among neigh- boring populations. On the other hand, Suzuki (1958) re- ported that the Okhotsk people were morphologically closer to the Eskimo people than the Aleut. Mitsuhashi and Yamaguchi (1961) found that skeletons of the Okhotsk people have characteristics specific to those of northeastern Asian people. These studies revealed that the morpholog- ical characteristics of the Okhotsk people were clearly different from those of the Ainu people currently living in Hokkaido. In addition, the morphological characteristics of the Okhotsk people are similar to those of the Nivkhi and Ulchi people that are currently distributed around Sakhalin and downstream of the Amur River (Yamaguchi 1974; Ishida 1988, 1996; Kozintsev 1990, 1992). The final con- clusion of the anthropological status of the Okhotsk people, however, has not yet been determined.

On the other hand, evidence of the occurrence of bear-sending ceremonies, as also seen in the Ainu culture, was found from archaeological sites of the Okhotsk culture (Utagawa 2002). In many cases, the skulls of brown bears were enshrined in bone mounds located within houses of the Okhotsk culture. This is a special custom that is not seen in archaeological sites of other cultures in Japan. The ritual is thought to be a proto-type of ‘‘Iomante’’, which was performed as a bear-sending ceremony in the Ainu culture. Ancient DNA analysis of the skulls of brown bears, excavated from an Okhotsk culture site on Rebun island, northern Hokkaido, showed that there were cultural ex- changes through bear cubs between the Okhotsk people and the Epi-jomon people (Masuda et al. 2001), which are archaeologically considered to be direct descendants of the Jomon people, and lived from the third century BC to the seventh century AD in southern Hokkaido. However, the custom of enshrining bears did not occur in the Satsumon culture followed by the Ainu culture. These facts suggest that the Okhotsk culture joined the Satsumon culture in Hokkaido, resulting in establishment of the Ainu culture (Utagawa 2002). …To investigate the phylogenetic relationships between the Okhotsk people and modern Asian populations, the NJ relationships among the 17 Asian populations were con- structed (Fig. 3). In this phylogenetic tree, the Okhotsk people were clustered with the Nivkhi, Ulchi, Negidal, Koryak, and Even. Among them, the Nivkhi and Ulchi were much closer to the Okhotsk people, and clustered with more than 70% bootstrap values. The close relatedness among the three populations was in congruence with the high degree of sharing of mtDNA haplotypes. On the other hand, the Ainu people were phylogenetically distant from the Okhotsk people (Fig. 3). However, the dA distance

(0.068%, Table 3) between the Okhotsk people and the Ainu was smaller than those between the Okhotsk and other populations except the Nivkhi and Ulchi. Moreover, multidimensional scaling analysis (two-dimensional dis- play, Fig. 4) of the genetic relationships among the 17 Asian populations based on dA distances showed that the Nivkhi, Ulchi, Negidal and Ainu were much closer to the Okhotsk people than the other Asian populations. These findings demonstrate that the Okhotsk people are closely related to modern populations distributed around the Sakhalin and downstream of the Amur River as well as to the Ainu people of Hokkaido.Among haplotypes 12, 13 and 14 identified from 11 Okhotsk people, a unique combination of four transitional mutations (16189C- 16231C-16266T-16519C for types 12, 13 and 14) was shared and regarded as the motif sequence for mtDNA haplogroup ‘‘Y1’’ reported by Kivisild et al. (2002). Recent studies have shown that most people with haplogroup Y1 are distributed in northern Asia and Siberia (Schurr et al. 1999; Kivisild et al. 2002). Moreover, Adachi et al. (2006) reported that haplogroup Y occurred in the Ainu of Hokkaido but not in the Jomon people of Hokkaido. In the present study, we found that the Okhotsk people shared haplogroup Y1 at a similar frequency (30%, 11/37) to the Nivkhi (35%, 20/57) and the Ulchi (31%, 27/87) (Table 2). The result also suggests that the Okhotsk people are genetically closer to the Nivkhi and Ulchi because of the similarity in the frequencies of haplogroup Y1 between them. Moreover, haplogroup Y1 was shared also by the Ainu (6%, 3/51) (Table 2). That the frequency of Y1 is higher in the Okhotsk people (30%) than the Ainu (6%) suggests gene flow from the Okhotsk people to the Ainu. In addition, other haplotypes clarified to haplogroup Y1 were found: for example, two types from two individuals of the Ulchi, two types from six individuals of the Nivkhi, and one type from seven individuals of the Ainu. When these numbers are included, the same direction of gene flow is still apparent. Tajima et al. (2004) examined mtDNA phylogeny of modern Asian people (not including the Okhotsk people) and reported that there was gene flow from the Nivkhi to the Ainu. The present study demon- strates that the Okhotsk people were an intermediate in the gene flow from the Nivkhi to the Ainu.

In previous morphological studies, Mitsuhashi and Yamaguchi (1961) reported that skeletons of the Okhotsk people had morphological characteristics similar to those of northeastern Asian people. In addition, Yamaguchi(1974) and Ishida (1988, 1996) reported, based on cranial measurements, that the Okhotsk people were closer to populations that are currently distributed downstream of the Amur River. Moreover, Utagawa (2002) reported that evidence for the occurrence of bear-sending ceremonies, as seen in the Ainu culture, was found from archaeological sites of the Okhotsk culture. Rituals using brown bears are thought to be one proto-type of ‘‘Iomante,’’ which has been performed as a bear-sending ceremony in the Ainu culture. Therefore, archaeologists have generally assumed that the Okhotsk culture joined the Satsumon culture (eighth to fourteenth centuries; direct descendants of the Jomon people in Hokkaido) resulting in establishment of the Ainu culture. The direction of gene flow obtained in the present study is in agreement with the interpretation based on previous morphological and archaeological data. These facts demonstrate that the Okhotsk people could have originated from northeastern Asian populations such as the Nivkhi and Ulchi currently living around Sakhalin and downstream of the Amur River, and support the hypothesis that the Okhotsk people could have joined the Satsumon people resulting in the Ainu culture.

Kikuchi (2004) reported that walrus tusks excavated from archaeological sites of the Okhotsk culture could have been brought from the ancient Koryak culture to the Okhotsk culture, because walrus are currently distributed in the Arctic sea and the Bering sea. In the present study, the Okhotsk people were found to have some genetic affinities with the Koryak and the Even living around the Kamchatka peninsula (Table 2; Fig. 3). These facts suggest that there were genetic and cultural exchanges between the Okhotsk people and the Koryak and Even. …Unique maternal genetic features of the Okhotsk people identified by ancient mtDNA analysis demonstrated their genetic differentiation and some genetic affinity with geographically neighboring modern populations such as the Nivkihi and Ulchi.…

Noboru Adachi, et al., Ethnic derivation of the Ainu inferred from ancient mitochondrial DNA data, 2018Results of this study:”indicate that the Ainu still retain the matrilineage of the Hokkaido Jomon people. However, the Siberian influence on this population is far greater than previously recog- nized. Moreover, the influence of mainland Japanese is evident, especially in the southwestern part of Hokkaido that is adjacent to Honshu, the main island of Japan.

Discussion: Our results suggest that the Ainu were formed from the Hokkaido Jomon people, but subsequently underwent considerable admixture with adjacent populations. The present study strongly recommends revision of the widely accepted dual-structure model for the population his- tory of the Japanese, in which the Ainu are assumed to be the direct descendants of the Jomon people. ……, recent morphological and genetic studies (e.g., Hanihara, Yoshida, & Ishida, 2008; Hanihara, 2010; Ishida, Hanihara, Kondo, & Fukumine, 2009; Sato et al., 2009; Shigematsu, Ishida, Goto, & Hanihara, 2004) have indicated that the Siberian influence via the Okhotsk culture people on the Ainu significantly affected the latter’s genetic structure. The Okhotsk culture people are thought to have migrated from north- eastern Eurasia and been distributed in the coastal regions of northern and northeastern Hokkaido as well as southern Sakhalin during the 5th to 13th centuries AD (Amano, 2003). On Hokkaido, this culture was rap- idly diminished by the invasion of Satsumon culture people at the end of the 9th century. As a result, Okhotsk culture had almost disappeared by the beginning of the 10th century. However, in the easternmost part of Hokkaido, the Okhotsk culture transformed into the Tobinitai culture under the strong influence of the Satsumon culture, and this culture con- tinued until the beginning of the Ainu era (Segawa, 2007).

Recently, we also confirmed the considerable genetic influence of the Okhotsk culture people on the formation of the modern-day Ainu.

We found that mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups A, C, and Y, which are shared by the modern-day Siberian populations, Okhotsk cul- ture people, and the modern-day Ainu, are not observed in the Hokkaido Jomon people (Adachi et al., 2011)…Genetic characteristics of the Ainu mtDNAs

Twenty-one haplogroups and their subhaplogroups were identified in 94 Edo Ainu individuals (Supporting Information Table S1). As described ear- lier, conventionally, the Ainu are considered to be descended from the Hokkaido Jomon people, with little admixture with other populations. Among the haplogroups observed in the Hokkaido Jomon (N9b1, N9b4, N9b*, D4h2, G1b*, M7a2, M7a*; Adachi et al., 2011), haplogroups N9b1, G1b*, and M7a2 are also observed in the Edo Ainu. Above all, haplogroup N9b1, which is the most frequently observed haplogroup in the Hokkaido Jomon people (55.6%, 30 of 54 individuals; Adachi et al., 2011), is also observed at a relatively high frequency (20.2%, 19 of 94 individuals) in

the Edo Ainu. These findings indicate the genetic continuity between the Hokkaido Jomon and the Ainu. This possible genetic continuity is corro- borated by Y chromosome DNA analysis of the modern Ainu. Y chromo- somal DNA haplogroup D1b, which is considered to be a strong candidate for the Jomon paternal lineage, was observed at high frequency in the modern Ainu (Hammer et al., 2006; Tajima et al., 2004).

However, there is a crucial difference between the Hokkaido Jomon people and the Ainu. Four haplogroups (N9b4, N9b*, D4h2, M7a*) are missing in the Edo Ainu, whereas they have 19 haplogroups that are not observed in the Hokkaido Jomon. This raises questions about the conventional hypothesis that the Ainu are the direct descendants of the Hokkaido Jomon people.

To clarify the matrilineal genetic relationship between the Edo Ainu and the other populations, pairwise Fst values between each pair of pop- ulations (Supporting Information Table S2) were calculated from the mtDNA haplogroup frequencies of the Edo Ainu and the 14 ancient and modern-day East Asian and Siberian populations (Table 1, Figure 1). In the frequency-based clustering of compared populations determined by neighbor-joining based on the Fst values described earlier, the Ainu of the Edo era was located almost in the median center between the Hok- kaido Jomon/Udegey cluster and the Lower Amur region cluster includ- ing the Okhotsk culture people (Figure 4). This confirmed our hypothesis (Adachi et al., 2011) that the genetic characteristics of the Ainu are based on the Hokkaido Jomon people and the subsequent input of Lower Amur region Siberian genes through the Okhotsk culture people. However, when examining in detail the haplogroups observed in the Ainu examined in the present study, haplogroups M7a1, M7b1a1a1, D4 (except for D4h2), M8a, Z1a, M9a, F1b, N9a, A5a, and A5c are observed neither in the Hokkaido Jomon nor in the Okhotsk culture people. This suggests the presence of populations other than the Hokkaido Jomon and the Okhotsk culture people that contributed to the formation of the Ainu. Mainland Japanese and the native Siberians are considered to be the major candidates for the origin of these haplogroups because of the proximity of their distributions to Hokkaido. …the results of mtDNA analysis of the Edo Ainu suggested the multiple origins of this population. This possible multiplicity of origins of the Ainu is considered to be an important factor behind their regional differences.DISCUSSIONNowadays, among the theories explaining the population history of the Japanese, the dual-structure model proposed by Hanihara (1991) is the most widely accepted.However, the results of our study suggest that the later admixture of Ainu with other populations than Jomon people was more consider- able than it was proposed until today.

First, our results showed that the genetic influence of the Okhotsk culture people on the Ainu is significant. The proportion of Okhotsk-type haplogroups in the Edo Ainu was 35.1%, which is as high as that of the Jomon-type haplogroups (30.9%). This suggests that the Okhotsk culture people were one of the main genetic contributors to the formation of the Ainu.

Moreover, intriguingly, a genetic contribution of the mainland Japanese to the Edo Ainu is evident (28.1%), which is almost as considerable as those of the Jomon and the Okhotsk culture people. As referred to above, conventionally, the genetic influence of the mainland Japanese on the Ainu is considered to have been limited until the Meiji government started sending settlers to Hokkaido as a national policy in 1869. However, our findings cast doubt on this accepted notion.

In addition, Siberian-type haplogroups are observed in the Edo Ainu. Although their frequency is low (7.3%), as described earlier, the existence of these haplogroups may hint at the continuity of the genetic relationship between the Ainu and native Siberians even after the Okhotsk culture disappeared from Hokkaido. However, the number of Okhotsk people who were genetically analyzed is still small (n 5 37; Sato et al., 2009), so it is possible that these haplogroups will be identified in the Okhotsk people in further study.

Regional differences of the Ainu

By classifying the mtDNA haplogroups into four types as described earlier, regional differences of the Ainu people were highlighted. Judging from the data shown in Table 2, the high frequencies of Jomon-type haplogroups in northeastern/central Hokkaido (44.2%) and the high frequencies of mainland Japanese-type haplogroups in southwestern Hokkaido (37.3%) might be plausible reasons for these regional differences.

This result is consistent with the result of a morphological analysis by Ossenberg et al. (2006). They described that, among the Ainu in Hokkaido, individuals in southeastern Hokkaido (this area is contained within our category of “northeastern/central Hokkaido”) are the closest to the Jomon people, whereas the individuals in western Hokkaido (this area is included within our category of “southwestern Hokkaido”) are the closest to mainland Japanese. This result is considered reasonable, given the geographical proximity of southwestern Hokkaido to the main island of Japan.

However, surprisingly, there were no regional differences in the frequencies of the Okhotsk-type haplogroups (35.3% in southwestern Hokkaido and 34.9% in northeastern/central Hokkaido). This indicates that the genetic influence of the Okhotsk culture people diffused rapidly in the fledgling Ainu.

As described earlier, Segawa (2007) stated that the invasion of the Satsumon culture people into the areas inhabited by the Okhotsk culture people and the subsequent decline of Okhotsk culture occurred rapidly. The Okhotsk culture people were considered to have been assimilated rapidly into the Satsumon culture during this process, and became part of the basis of the Ainu.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

In the current study, we clarified that the Ainu were established from the Hokkaido Jomon people and subsequently underwent considerable admixture with adjacent populations. The present study strongly recommends review of the widely accepted dual-structure model regard- ing the population history of the Japanese, in which the Ainu are assumed to be the direct descendants of the Jomon people. However, the causes of the regional differences in the genetic influence of the Okhotsk culture people on the Ainu remain unresolved by mtDNA analysis. Nuclear genome analysis using next-generation sequencing is expected to be helpful to resolve this issue.…